Rabih Abou-Khalil - Pressestimmen

Rabih Abou-Khalil

Rabih Abou-Khalil

>>> Pressefotos

Tagblatt Anzeiger, 31.05.2017

Rabih Abou-Khalil über Mythen, Musik und Mitteilungsbedürfnisse

Die Fragen stellte Jürgen Spieß

Er steht wie kaum ein anderer für eine Musik, die sich aus arabischen Wurzeln speist und sowohl europäische Klassik als auch amerikanischen Jazz involviert: Rabih Abou-Khalil gastiert am Sonntag, 18. Juni, um 20 Uhr mit seinem Trio in der Tübinger Stiftskirche.

Der in München lebende Rabih Abou-Khalil weiß genau, wer in den Rahmen seiner Vorstellungen passt. Er hat mit Charlie Mariano, Glen Velez oder Glen Moore zusammengearbeitet und schreckt auch nicht vor ungewöhnlichen Begleitern zurück: So etwa der italienische Akkordeon-Virtuose Luciano Biondini und der US-amerikanischen Jazz-Perkussionist Jarrod Cagwin, mit denen er sein aktuelles Programm „Hungry People“ in Tübingen vorstellt. Der Weltenbummler, der mit klassischer arabischer Musik in Beirut aufwuchs und 1978 vor dem libanesischen Bürgerkrieg flüchtete, um in München Querflöte zu studieren, hat sich ein Konzept zusammengebaut, das sich ungeniert in West und Ost bedient. Wir sprachen mit dem deutsch-libanesischen Künstler vor seinem Auftritt in Tübingen.

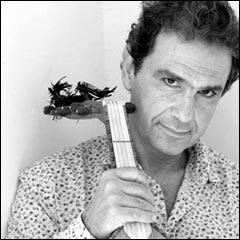

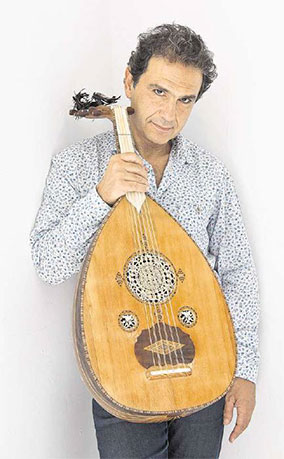

Rabih Abou-Khalil stellt in Tübingen sein aktuelles Programm unter dem Titel „Hungry People“ vor. Bild: Spieß

TAGBLATT ANZEIGER: Herr Abou-Khalil, hat Ihr Name eigentlich eine bestimmte Bedeutung, wie das im Arabischen oft der Fall ist?

Abou-Khalil: Nur der Vorname, der bedeutet Frühling.

Wie kamen Sie zum Jazz? Waren Ihre Eltern ebenfalls Musiker?

Nein, mein Vater hat gedichtet, aber das Bedürfnis, sich auszudrücken, habe ich schon von meinen Eltern geerbt. Dabei geht es gar nicht mal so sehr um die Fähigkeit, etwas spielen zu können, sondern eher um den Zwang, sich künstlerisch ausdrücken zu wollen. Dieses Mitteilungsbedürfnis ist mir vermutlich mit in die Wiege gelegt worden.

Mit über einer Million CD-Verkäufen und jeder Menge Auszeichnungen zählen Sie inzwischen zu den bekannten Namen im Jazz. Hat sich dadurch etwas für Sie verändert?

Im Vergleich zu früher hat sich eigentlich nicht viel verändert. Ich kann mich auch heute noch darüber wundern, dass es genug Leute gibt, die meine Musik hören wollen. Es bedeutet mir sehr viel, dass ich auf dieser persönlichen Ebene Leute erreichen kann, die von meiner Musik berührt sind. Das erlebe ich nach wie vor als Herausforderung und Gratwanderung zugleich. Denn die Zuhörer sollen auf der einen Seite nicht das Gefühl bekommen, dass da ein Lehrer auf der Bühne sitzt, auf der anderen Seite darf Musik nie in Banalitäten verfallen.

Haben Sie eine Botschaft, die Sie vermitteln wollen?

Nein, denn letztendlich unterstellt eine Botschaft der Musik einen Zweck. Mir geht es vor allem um das Künstlerische. Wenn Leute in meiner Musik etwas finden, dann freut mich das natürlich, aber daraus eine Botschaft abzuleiten, halte ich für übertrieben.

Sie kamen aus dem Libanon nach Deutschland. Warum gerade Deutschland?

Das war eher Zufall, weil zu dieser Zeit ein Freund von mir nach Deutschland ausgewandert ist. So war es etwas leichter für mich, da ich nicht bei Null anfangen musste. Dennoch war es nicht einfach, denn es war immerhin das erste Mal, dass ich von meiner Heimat weg war und dann gleich in einem völlig fremden Land. Ich musste mich erst einmal zurechtfinden und das ist gar nicht so einfach, wenn man aus dem Orient nach Bayern kommt.

Lag das an Bayern, das ja nicht gerade für seine Interkulturalität bekannt ist?

Nein, mit Bayern speziell hat das nichts zu tun. In Baden-Württemberg, Frankreich oder England hätte ich ähnliche Schwierigkeiten gehabt. Ich kann mich sowieso nicht beklagen, denn ich bin in einer wesentlich privilegierteren Lage als die meisten anderen Ausländer, die hier leben und habe als Musiker mit ganz anderen Leuten zu tun, als wenn ich beispielsweise Arbeiter wäre. Insofern habe ich auch mit Rassismus wenig Probleme und habe selbst noch nichts Negatives erlebt. Außerdem ist es meiner Meinung nach ein Mythos, dass es in Deutschland mehr Rassismus gäbe als in anderen Ländern dieser Welt.

Bekommen Sie den alltäglichen Rassismus zu spüren?

Natürlich, aber ich bin Realist genug und glaube nicht, dass wir in absehbarer Zeit eine Welt haben werden, in der es keinen Rassismus geben wird. Inzwischen bin ich sowieso überall Ausländer, selbst wenn ich nach Hause in den Libanon gehe.

Basler Zeitung, 20.01.2015

Zwischen Rastlosigkeit und Neugierde

Von Stefan Strittmatter

Rabih Abou-Khalil ist Oud-Grossmeister, Grenzüberschreiter und Herzensmusiker

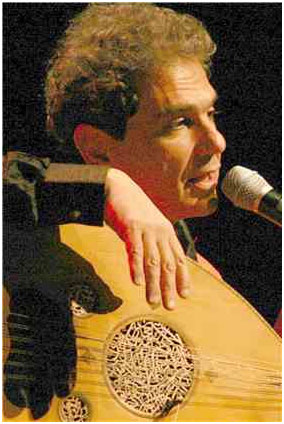

Der Virtuose und seine Oud. Rabih Abou-Khalil sagt: «Es war mir damals wie heute nicht klar, wo mein Arm anfängt und wo das Instrument aufhört.»

Es ist ein denkbar undankbares Instrument:

Der Korpus der Oud ist klobig,

ihre oval zulaufenden Rundungen sind

prädestiniert, dass sie gerne vom Bein

rutscht, und der bundlose Hals ist so

kurz, dass die Greifhand mit absoluter

Millimetergenauigkeit agieren muss.

Dennoch hat Rabih Abou-Khalil genau

dieses Instrument für sich gefunden – in

einem Alter, als die arabische Knickhalslaute

noch grösser gewesen sein

muss als ihr fleissiger Schüler.

Was der 57-Jährige aber mit seiner

Oud anzustellen vermag, transzendiert

das Instrument: Töne bekommen eine

vokale Qualität, wenn er in eine Note

hineingleitet. Läufe, die mit rasend

schnellem Stakkato-Anschlag über das

Griffbrett huschen, erzeugen einen

regelrechten Rausch. Und stets

schwingt Fernweh als Kolorit mit.

Im BaZ-Interview erklärt der Virtuose

sein Verhältnis zur Oud folgendermassen:

«Es ist genauso schwierig

für mich, die Frage nach meiner Beziehung

zu meinem Arm oder meiner Nase

zu definieren.» Er habe, so Abou-Khalil

weiter, das Spiel in sehr jungem Alter

gelernt. Und: «Es war mir damals wie

heute nicht klar, wo mein Arm anfängt

und wo das Instrument aufhört.»

Die gesammelten Einflüsse

Auf mittlerweile zwei Dutzend

Alben hat der gebürtige Libanese sein

Können eingefangen. Und dabei einen

steten Wandel durchlaufen. Anfangs –

auf «Compositions & Improvisations»

(MMP, 1981) oder «Bitter Harvest»

(MMP, 1984) – zeigte er sich noch stark

der östlichen Tradition verhaftet. Bald

jedoch – spätestens ab seinem Enja-

Records-Debüt «Al-Jadida» (1990) – ist

Abou-Khalils Spiel zu gleichen Teilen

von arabischen Rhythmen und Modi

und von westlicher Improvisation und

Interaktion geprägt.

Die Freude am Grenzgängertum

zieht sich nicht nur durch das musikalische

Schaffen des Mannes, der 1978 vor

dem libanesischen Bürgerkrieg nach

München geflüchtet ist. Seither pendelt

er mit seiner Frau zwischen München

und Südfrankreich – wenn er nicht

ohnehin gerade für Projekte oder Tourneen

um den halben Globus reist.

Die gesammelten Einflüsse schlagen

sich jeweils in den Kompositionen des

Oud-Meisters nieder: «In Libanon wird

behauptet, meine Musik klänge westlich,

für den Westen klingt sie orientalisch.

Wahrscheinlich stimmt beides

und auch wiederum keines.» Er selber

denke nicht in Kategorien, wenngleich

ihn Schubladisierungen wenig störten:

«Das erleichtert das Wiederfinden

beliebter Musikrichtungen.»

Abou-Khalil wurde früh als Weltmusiker

bezeichnet, noch bevor Peter

Gabriel Anfang der Achtziger mit seinem

Label Real World der Verbreitung

der Bezeichnung World Music zu weltweiter

Beachtung verhalf. Entsprechend

wenig mag sich der Musiker auf

eine einzige Bandbesetzung festlegen:

Mal musiziert er mit einer mann- und

dezibelstarken Blaskapelle, dann im

Quartett mit Obertonsänger, Schlagzeug

und Tuba, schliesslich wieder ganz

alleine.

Eine kleine Welt

Was steckt hinter dem Drang nach

dem Besetzungswechsel im Jahrestakt

– Neugierde oder Rastlosigkeit?

«Ich glaube, beides. Die Tatsache, dass

die Welt so klein und zugänglich geworden

ist, ist eigentlich eine wunderbare

Sache. Da gibt es so viele Musiker und

Musiken, dass man mehre Leben

braucht, um sich auch nur annähernd

damit beschäftigen können. Da weiss

ich nicht einmal, wo ich aufhören soll.»

Vorerst denkt der Herzensmusiker

aber ohnehin nicht ans Aufhören.

Diesen Freitag gastiert er im Trio mit

Luciano Biondini am Akkordeon und

Jarrod Cagwin an der Perkussion in der

Zürcher Kirche Neumünster. Und im

Mai stellt er im Raumen des Jazzfestivals

Basel in der Kaserne seine fünfköpfige

New Group vor.

Egal, in welcher Konstellation

Abou-Khalil musiziert: Konstant bleiben

Detailliebe und Humor. In aufwendiger

Arbeit versieht er seine Alben

jeweils mit ausführlichen Begleittexten

und wunderschön gestalteten Frontbildern

(charakteristisch ist der Einbezug

von Goldprägung). Songtitel wie

«Ma muse m’amuse», «Dr. Gieler’s

Wiener Schnitzel» oder «Mourir pour

ton décolleté» bringen den Schalk zum

Ausdruck, den Abou-Khalil mit einem

seiner Idole teilt: «Frank Zappa war

schon in Libanon einer meiner grossen

Vorbilder. Humor ist zum Teil ein Ausdruck

des Absurden. Ich finde es leichter, in einer surreal-absurden Welt eben

dieses Surreal-Absurde auch so zu

sehen.» Zuweilen sei es nicht einfach,

sich diesen Humor zu bewahren,

schreibt der umtriebige Musiker, der

zum Zeitpunkt unseres schriftlich

geführten Interviews in Libanon weilt,

«wo der blutige Religionskrieg das Land

in zwanzig Jahren zerstört hat».

Die zerstörerischen Religionen

Auch zeigt sich der Wandler zwischen

Ost und West schockiert von den

Anschlägen in Paris: «Diese Ereignisse

haben wieder einmal verdeutlicht,

welch zerstörerische Kraft Religionen

haben.» Dann zieht Rabih Abou-Khalil

in gewandtem Schriftdeutsch eine

Parallele von der Inquisition zu den Entwicklungen

der letzten hundert Jahre,

um mit einem nüchternen Fazit zu

schliessen: «Ich vermeide es, eine Religion

über die andere zu erheben. Von

keiner haben wir einen positiven

Beitrag zur Menschlichkeit gesehen,

obwohl das alle behaupten.»

Auch wenn er das selber für sich nie

in Anspruch nehmen würde, so leistet

Rabih Abou-Khalil mit seiner grenzüberschreitenden

Musik vielleicht doch

einen kleinen Beitrag zum gegenseitigen

Verständnis der Kulturen.

Doch verfolgt er mit seinem Spiel

kein Ziel, er spielt das denkbar undankbare

Instrument, weil er nicht anders

kann: «Die Oud ist das Erste, das ich

morgens in die Hand nehme, und das

Letzte, das ich abends weglege»,

beschreibt Rabih Abou-Khalil seinen

Tagesablauf. Und fügt an: «Für meine

Frau ist das nicht immer einfach.»

Mainspitze, 26.09.2014

„Quintet Méditerranée“ fesselt das Publikum im Rüsselsheimer Theater

Von Klaus Mümpfer

RÜSSELSHEIM - Die ersten in Akkordgriffen angerissenen Melodiefragmente auf der elfsaitigen Oud klingen fremdartig und doch vertraut. Es sind nahöstlich geprägte Stimmungen, wie man sie seit Jahrzehnten von dem im Libanon geborenen Virtuosen Rabih Abou-Khalil auf der arabischen Kurzhalslaute kennt.

Foto: Vollformat/Volker Dziemballa

Doch dann steigt Luciano Biondini mit dem Akkordeon ein, der Rhythmus beschleunigt sich, wird von Jarrod Cadwin auf der Rahmentrommel und dem Schlagzeug forciert. Bereits bei den ersten Akkorden und Rhythmen von „When Frankie shot Lara“ ist das Publikum auf der gefüllten Hinterbühne des Rüsselsheimer Theaters von der Musik des „Quintet Méditerranéen“ gefesselt.

Kraftvoll und sanft

Bei „Ja nao da como este“ fügt sich der Fado-Sänger Ricardo Ribeiro mit kraftvoller und tragender Stimme in die polymetrischen Interaktionen der Musiker ein. Das „como um rio“ wird geprägt von den ständigen Wechseln zwischen der balladesken Fado-Tradition und den rasanten Läufen auf der Oud. Die sanfte Einleitung eines Liebesliedes wird von dem Bass-Gegrummel des Saxofonisten und sardischen Sängers Gavino Murgia unterlegt, während Biondini auf dem Knopf-Akkordeon ein tänzerisch beschwingtes Solo beiträgt. „Al lua num quarto“ hebt sanft mit dem Akkordeon an. Melancholisch wie dessen Klänge ist auch der Gesang, erfüllt mit der schmachtenden Sehnsucht des „saudade“, jener schwer zu definierenden Stimmung, die auch der Zugabe „Amarrado a saudade“ den Titel gibt.

Alle Kompositionen des fast zweistündigen Konzertes in der Rüsselsheimer Jazzfabrik stammen aus der Feder von Rabih Abou-Khalil. Zwar hat er Künstler aus den Mittelmeer-Anrainer-Staaten Portugal, Italien, Sardinien um sich versammelt und Elemente aus den Kulturen dieser Länder aufgenommen, doch die Diktion des Libanesen prägt Sound und Rhythmus des „Quintet Méditerranéen“. In dieses Konzept fügt sich auch der amerikanische Schlagzeuger Cagwin ein, der zwar mit seinen Trommeln harte Akzente setzt sowie hin und wieder schier zu explodieren scheint, doch mit der großen und der kleinen Rahmentrommel dem nahöstlichen Metrum frönt. In einigen Passagen nähert sich das Quintett in verflochtenen und komplexen Kollektiven einem scheinbar geordneten Chaos.

Humorvoll stellt der Oud-Spieler Abou-Khalil seine Partner vor, moderiert das Programm und erklärt bisweilen ironisch seine Musik. „Wenn in der Vertonung der portugiesischen Gedichte vom Tod die Rede ist, spiele ich eine Oktave tiefer, wird von der Liebe gesungen, eine Oktave höher“, erläutert er belustigt. „Em portugués“ ist der Titel eines Projektes, aus dem das Quintett auch beim Rüsselsheimer Konzertes schöpft. Er habe es auf Bitten des Direktors des Nationaltheaters Porto, Ricardo Pais, mit der Vertonung portugiesischer Gedichte kreiert, erzählt der Libanese. Wesentlichen Anteil am Gelingen hat sicher Ricardo Ribeiro, mit dem Rabih Abou-Khalil, in einer ersten Zugabe im Duo von der verlorenen Jugend singt und spielt.

Bridging Cultural Divides, 11.12.2013

Rabih Abou Khalil: Bridging Cultural Divides

Von Nenad Georgievski

Rabih Abou Khalil is one of the most respected virtuoso oud players and composers whose wide range of interests and insatiable curiosity for new music from around the globe has significantly enriched his own work. His music is his own universe where an ongoing dialogue between Khalil and the rest of the world has been occurring. He was born and raised in the cosmopolitan climate of Beirut, Lebanon, before the civil war that ravaged his homeland forced him to leave for Germany where he studied classical flute. In the past 30 years and with 20 albums behind he has carved out a unique niche where his works explores melodies and rhythms that incorporate compositional and improvisational elements that are common in Arabic, classical and jazz music. His philosophy of using music as a tool to bridge cultural divides has won over audiences everywhere. Among some of his pan-global projects is his recent venture with cellist Yo-Yo Ma's Silk Road band and has been composing music for various classical orchestras. Khalil, who has performed several times in Macedonia at the Skopje Jazz Festival, recently performed at the Bitola World Music Festival when he premiered Hungry People (Harmonia Mundi, 2012), a reaction to happenings during the "Arab Spring" occurrences as well as other things that have been happening during that time. Khalil was in a jovial mood during the interview that was conducted before the concert in Bitola and he is a person of depth and thoughtfulness, spiked with a healthy dose of humor, which also has won him audiences worldwide, much like the one at the festival.

All About Jazz: Your career has been characterized by endless risk takings, cross cultural endeavors that have reflected in unique music. What was it that inspired you to take a different route, to go upstream and not following a strict tradition thus entrenching into your own culture as many artists do these days?

Rabih Abou Khalil: Maybe it is because I am entrenched in my culture. That's the reason. The musicians I play with, each one of them is profoundly 'in' their own culture. I think this is the only way this could work, to be comfortable with your own culture and then to be able to transcend it, in order to be able to do something more. When people ask me, which is natural, about how and why, I really have no plan or I don't even try to do anything. For me, music is an emotional expression and not stylistic one. Therefore, naturally, everything I hear affects me. Everything I see affects me. Everything I feel affects me. But I didn't have a plan where I would bring some multiculturalism. I was only working with musicians I could work with. They just happened to be from everywhere. So, if I hear somebody in Portugal, I'll say great, I would like to work with this guy. He sounds like I can relate to him. Here is someone from a different culture. I lived for a long time in Germany, but I played very little with German musicians because I didn't care if I live in Germany that I should necessarily play with them. That would have been practical if I had chosen German musicians. I wasn't trying to avoid them as much as I was looking for personalities.

And when people speak about multiculturalism, it has never been different since humans left Africa and spread throughout the world. There is no pure culture. Anyone who thinks there is a pure culture... that is a fascist thinking. There is nothing pure. Everybody moved from one place to another—the Greeks, the Romans, everyone, everywhere. You can see blond people in Lebanon. My grandfather was blond and had blue eyes, and he comes from a village in the mountains in Lebanon. Multiculturalism is the basis of the human culture. Without it we wouldn't go even one step ahead. Look at the Americans and their culture. It is not a culture at all. They are a bunch of people from around the world and they got together because of a certain interests to do some things.

So the meeting of cultures, of people from different corners of the Earth has always made cultures grow. Look at jazz—it is a meeting of Africa and Europe (not because they wanted to). The whole Roman Empire brought slaves from everywhere. In Rome, if you look at the Roman times it was the pinnacle of multiculturalism. They had slaves from everywhere. Even the emperors were from different corners of their empire—from Syria, Germania, everywhere. And each of them had added something to whatever was there. So when Mussolini came and said we want to keep the Italian culture pure, wait a minute—(laughs) this is already a mix of so many things. Thinking that we should keep things very pure is very, very wrong. Nothing grows when it is pure. You don't drink pure coffee. You put water in it, milk, and sugar. Nothing we do is pure. Not even the emotions we have are pure. It's always a mix of many things. It was a long answer (laughing)!

AAJ: What was it like to be growing up in the 60s and 70s in a cosmopolitan city that pre-civil war Beirut was? Did that surrounding influence your way of thinking?

RAK: I think more than growing up in Beirut, really, was growing up with a certain mindset in the family. My father came from a small village in Lebanon and like it is the case sometimes with people from different corners of the world, he was interested in everything. He studied 8 languages which he spoke rather well. It wasn't something that obviously ran in the family as his father worked with leather. But he was interested in that and he was not a religious man. So probably that helped all of us to be open to everything. We weren't thinking, "Oh they are different," so I think that was the part that made me at least feel I can open and take everything I need and to mix with different ideas. And it was of course that Lebanon was open back then. Actually, the whole of the Arab world was very open back then. It was not like it is today. Today we look at it and we think of it as something awful. Maybe that is true, but back then it was much more open. The Arab societies knew more about Europe than Europeans knew about us. That of course, helped in understanding them. And you know, my father is a poet and he was very much interested in everything that had to do with the word. That also transported itself into my thinking as well as the thinking of all of us. Of course today he would be the wrong person in that area (laughing).

AAJ: What are people's reactions in the Arab world or beyond to your endeavors in different music from around the world and then incorporating those influences into your own?

RAK: I have been receiving very mixed reactions, like with everything you do. It's like when everyone agrees that something is good then it must be bad. People never all agree when something is good. There are all kinds of reactions. There are people who think that this is great and that this is something new and there are people that say, "Oh, but you have to keep with the tradition," which is always a question I'm very touchy about, as when it comes to tradition, there is no such thing. What is traditional today was revolutionary yesterday, and if you study anything, if your memory goes anywhere beyond one generation you will realize that nothing was built the in the same way. Even if you try and make it and keep it the same, it just never stays the same. Everything changes. And so thinking that you have to stick to something actually kills it and suffocates it more than lets it grow.

AAJ: When you delve into other people's cultures and music you are passing through different spiritual elements that are interwoven in those cultures? Does spirituality play any part in your music?

RAK: Spirituality is such an incredibly vague expression that is very, very difficult to define what it is. In fact, we speak about it very little. For me it is important and I think it is something more that keeps the group going than anything that we might call spirituality or tapping into other people's cultures or anything. I try to create families of the musicians that I work with. We are a family. We have been working together for 15 years now and we are still friends. We eat together, we sit together, we enjoy our time together, and we make music together that is something that is very likely to happen in the family. So if you want to call that spiritual, which in a way it is, and friendship is that and having the need to communicate each other, and still try to do new things every time we get to work together. We still play some of the old songs and every time it's different. We look at them from a different time and different perspective. So that has changed. So, spirituality, in terms of anything religious, I think there is no room for that in anything creative

AAJ: Your new record, Hungry People was inspired by recent happenings in the Arab world, like the Arab spring, among other things.

RAK: I think it is a reference to a lot of things, including the Arab spring. Actually, it was done during that period, and maybe more than a political thought, it is more an emotional one. Of course I suffer because of many things, mainly maybe because of the impossibility to choose a side because I'm not acceptable (laughs). But in terms of being hungry, I think, the idea of hungry things is something that is very broad. We are always hungry for new things, for trying new things, and not just about eating. The hunger for everything you need and want is what keeps people do whatever they do, for whatever reason, right or wrong. I think hunger is what keeps everybody going and wanting to do something. It's a driving force for anything. It's what has made us move.

AAJ: One of your recent projects was composing music for a silent movie, a powerful drama which was long thought to be lost, titled Nathan the Wise performed by the German Youth Orchestra.

RAK: That was music for a silent movie and was recently shown in Jerusalem. It was based on a book from the 19th century that was a basis for the movie. The book's title is Nathan the Wise and was written by Ephraim Lessing, a German author who lived in the 19th century. The book is about tolerance which was very new at the time when it was written in the late 19th century Germany. It is a parable of tolerance between basically three religions: Christianity, Judaism and Islam, and the story plays in the middle ages in Jerusalem. It was a reference to that. I have always admired the book and the story. It's a theater piece, a drama. So when the people actually asked me to do the music for the movie, which is a silent movie, the interesting thing about it was that the movie was never shown anywhere because the Nazis shut it away. They had enough power to do that in 1922 when it came out. The film was filmed in Munich and the first time it was shown the Nazi party said, "No, this is not okay," and it was prohibited. They found the only remaining copy in Moscow about 12 or 13 years ago. They took the copy and then they restored it. Then they asked me to do the music and I was very, very interested in doing that because it was a beautiful thing to do. That's how it happened, which I think the CD which was supposed to come out with the film, because it is difficult to understand it without knowing actually what's it about. But then, it just didn't work out.

AAJ: Has the film been out?

RAK: No, the film is not out, but you can see it at the museum it was shown at couple of times at three or four o'clock in the morning, which is the fate of these films (laughing). That is a pity because it is a beautiful film. It is two hours long. So, when I said yes, I will write the music for it, I said to myself, "It is a silent movie, what could be difficult here?" But writing two-hour material for an orchestra is not an easy task. To rehearse it, record it and actually do it was amazing. So far we played it twice to promote the film. It was wonderful. It would be nice if we could do it with the Macedonian philharmonic orchestra sometimes.

AAJ: You still have fond memories of playing with the orchestra at the Skopje Jazz festival in 2008?

RAK: Yeah, I had a great time doing that. I enjoy working in Macedonia. As you know I like working with people and the culture. I don't try to make my people, like the Frenchman to sound like an Arab or Italian. I'd rather like to see if we could find something that we could all speak about at the same time. And Macedonian music is close to my understanding and it is very easy to communicate with the orchestra regarding that side. It would be nice I could work with them again.

AAJ: It's your fourth performance here with various projects.

RAK: I feel understood here, funnily enough—musically understood. Usually people everywhere like my music and there is always a good response. Maybe it's because this place is also a mix of so many different cultures. Even the food! I can taste something and would think, "Oh my mother could have made this." So there are things that are similar, and in Macedonia, the music has a sense of rhythm that I feel very connected to. It was very easy to play because when I usually play with European musicians, the biggest problem is always the rhythm. I try to make them understand that it is not 1-2-3-4. It is not about this, but how it swings, and the rhythm which speaks. And I had no problem working with the Macedonian musicians. Of course, they are so easy to work with and then we can work on the music rather than technical parts.

AAJ: Because folk music, which is very popular, is what our DNA is made of, and everyone grew up with it. Some of them also play it in their spare time.

RAK: Of course, that's what everybody does and it's very special in Macedonia. It's very rare to see someone who doesn't play an instrument. And if he isn't playing, he is listening, which is the same thing. If you listen, you don't have to play. It's enough. This is very rare and I don't see that in any other country, not even the countries around Macedonia. There is something very special about this subject. It was there from the first moment that we played here. It was like... whoa... it's a different kind of audience.

AAJ: You also took part in a multicultural musical project led by cellist Yo-Yo Ma, The Silk Road projectwhich gathered musicians and composers from more than 20 countries in Asia, Europe and South and North America.

RAK: They called me because they knew my music and wanted to do this. When they asked me again, I was a bit overworked and I wrote another song for them. For me, I arrive somewhere and I sit and see what people are working with, and I just try to work on the music. I really don't think much about where they come from. I can sense what I'm comfortable with. I can sense people's strengths, what they do best. And I like to work with that, to start from there and to work on that. This was a mix of many different people. Everybody had weaknesses and strengths, trying to get something there. It was a lot of fun. We stayed at a wonderful place and when he came he came to France (I live in the south of France), I saw him there. In fact it was my birthday, so we celebrated it together, which was a lot of fun. He does things which are similar to what I do. We share our minds about it. He is more serious about the cultural impact. All I care about is the music, really. At the end of the day, for me these are nice side-effects. This is not what I'm really looking for. I want to do music as much as I can. In that sense I had a very good rapport with Yo-Yo Ma and he is maybe even one step further than that because for him, all of that is a project. I'm trying to invent a word for that eventually—a "musico-political" project. It connects two words and this is something I really lack, at least that I consciously lack. I don't really care where the people I work with come from—they can be blue, green, Christian, Jewish or Muslim. All I care is the music and to see how we can get it together.

AAJ: What the future holds for you?

RAK: That is a very difficult question because I don't even know where to begin that really. I have a new website now and will try to move on with a lot of things. I'm doing my own studio and I think I'll be doing more work at home. Now everyone is crying that they are not selling as many CDs as they used to, but now, we can do what we want to do. The commercial side of it is dying out, so maybe that will give us a chance to experiment more because now, we may not publish one CD a year, but we can do something every day.

Südkurier, 23.03.2009

Das Rabih Abou-Kahlil-Trio gastierte in Allensbach

Von Bettina Schröm

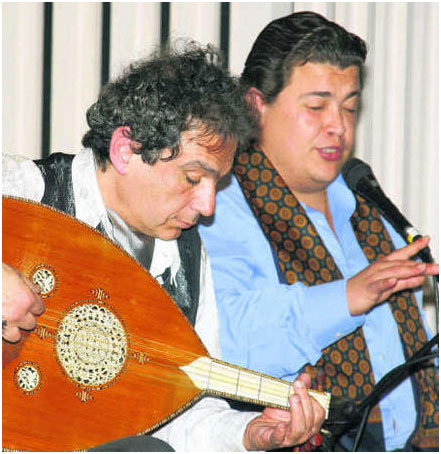

Oud-Star Rabih Abou-Kahlil mit Sänger Ricardo Ribeiro. | Bild: B. Schröm

„Und jetzt spielen wir ein Liebeslied.“ Das sagt er oft an diesem Abend in der ausverkauften Allensbacher Gnadenkirche, Rabih Abou-Kahlil, jener Musiker, der dafür gesorgt hat, dass in Europa fast schon jeder weiß, wie ein eigentlich archaisches, mit einem Federkiel zu spielendes Instrument klingt: die arabische Laute, al-ud oder schlicht Oud genannt. Abou-Kahlil hat sie mit allen denkbaren Instrumenten kombiniert, hat mit klassischen Musikern gespielt und ist auf Jazz-Festivals ein- und ausgegangen, ja, er ist mit einer der Hauptverantwortlichen für die Weltmusik-Welle, die seit Jahrzehnten den Markt überschwemmt.

Doch während vieles, was unter diesem seltsamen Begriff „Weltmusik“ unterdessen gehandelt wird, nur eine Umschreibung ist für eingängige Melodik, gespielt auf exotischen Instrumenten und unterlegt mit einem Hauch sehnsüchtigem Nachhall, kann man sie bei ihm immer wieder entdecken: eine unbekannte musikalische Welt.

Nun steht Abou-Kahlil erstmals mit einem Sänger auf der Bühne, Ricardo Ribeiro heißt er, blutjunger Portugiese, imposante Erscheinung und ein Meister des Fado, jener Musik gewordenen Melancholie seiner Heimat. Ihm hat Abou-Kahlil seine Vertonungen portugiesischer Liebesgedichte auf den Leib geschrieben, „das Ausgeflippteste, was ich bis jetzt gemacht habe“. Ribeiro singt sie mit halb geschlossenen Augen, belegter Stimme und einem beeindruckenden Tonumfang.

Und was daraus entsteht, ist kein romantisches Rührstück. „Em Português“, wie auch die gleichnamige CD mit Beteiligung von Michel Godard und Luciano Biondini heißt, ist ein Programm, das den Fado verbindet mit seinen arabischen Wurzeln. Ein wenig Wüstensand legt sich auf das kunstvolle Liebesleid, eine herbe Schönheit und ein pulsierender Rhythmus. Letzterer ist nicht zuletzt einem wunderbaren Mann zu verdanken, der auf einem schlichten Instrument zaubern kann: Jarrod Cagwin entlockt der Rahmentrommel virtuose Spielereien und lautmalerische Klänge. Dass seine Percussionskünste nicht alleine als Rhythmuselement dienen, ist eines der Geheimnisse des Trios, das ein bis auf kleinste Akzente abgestimmtes, perfektes Zusammenspiel betreibt, in dem die Oud einerseits den Gesang parallel begleitet, andererseits Funktionen der Rhythmusgruppe übernimmt – und immer wieder ansetzt zu atemberaubenden Soli. Denn auch das gehört zu diesem Abend der musikalischen Leidenschaften und ironischen Moderationen: eine absolute technische Souveränität.

Sie macht Stücke mit Titeln wie „Der Mond im Zimmer“, „Wie ein Fluss“, „Wenn ich dich lächeln sehe“ zu kleinen Ereignissen und natürlich das viel versprochene pornographische „No Mar Das Tuas Pernas“/ „Im Meer deiner Beine“, eine tolle Nummer, basierend auf einer minimalen absteigenden Melodielinie, voll diffuser Chromatik, überraschender Akzente und beunruhigendem Tremolo. Ja, er ist auch ein beeindruckender Komponist, dieser Libanese, der den deutschen Konjunktiv so gut beherrscht, dass er mit tiefer Stimme und schelmischem Lächeln die amüsantesten Wortspiele anstellen kann.

So schnell wollen ihn die Allensbacher, die ihn bereits 2008 bejubelt haben, nicht gehen lassen. Ein kleines Zugaben-Set muss schon sein, bevor man wieder hinabsteigt in den schnöden Alltag. Dabei kann das Glück so schlicht daherkommen: „Und jetzt spielen wir ein Liebeslied.“

MENÜ

MENÜ